The Rarest Beehive in the World

by Richard Wentzel

Reprinted from "Crown Jewels of the Wire", July 1994, page 5

25 Years of Collecting

Searching through the memories of my childhood, I can't recall a single

family vacation that didn't eventually end up alongside a set of railroad

tracks. It was, I suppose, only natural that we gravitate toward the "high

iron", given my family's railroading heritage. My great-grandfather was a

signal tower operator in my hometown of Millville, New Jersey, and my father

worked for many years as a railway postal clerk, serving in New Jersey and

eastern Pennsylvania.

So, on the first day of our annual summer vacation, the

year 1967, it came as no surprise that our destination was an isolated railroad

junction in rural southeastern New York state, a place by the name of Campbell

Hall. Here, where the New York, Ontario & Western once crossed the Erie,

would be the place where I received my initiation into the world of insulator

collecting.

As our station wagon rounded a bend in the road and pulled parallel

with the Erie-Lackawanna mainline, the excitement level of two little boys in

the back seat began to rise. My brother and I bounced out of the car almost

before it stopped. Dad looked at his "magic book" (employee timetable)

and pronounced that it would be a while before a train made its appearance here.

My mother dutifully began to set out the trappings of our "cinder

picnic". Now, it was time to explore!

No sooner had we crossed the tracks

and scrambled down an embankment when our great discovery was made. Lying on the

ground in unfamiliar repose was the very familiar form of a telegraph pole.

Never previously having had the opportunity to study one at such close range, I

had likewise never given any thought to the curious glass objects mounted atop,

now made so accessible. "What are these things, Dad?" I asked.

"Insulators," came the reply, "see if you can find something to

put them in."

I managed to locate a battered wooden bucket once used to

hold railroad spikes, and we proceeded to liberate as many specimens as would

fit into that container, plus a few more for our pockets. Most of the insulators we found that day were ice blue Whitall Tatum No.1' s, but the

small variety of shapes, colors and names were more than enough to capture my

youthful imagination and launch me into starting a collection.

In those early

days, it was quite easy to find new additions for my display shelf. Virtually

every trip along a railroad right-of-way yielded something different. We would

kick around the base of each pole, and in the surrounding underbrush where a

lineman might conceivably have thrown an outdated insulator. Success came so

often and was so sweet!

I was nothing short of full-tilt gung-ho about our

collecting expeditions. I'm reminded of an outing along the Reading Railroad

just outside of its namesake city . We were kicking up CD 147 spiral grooves

left and right. These were brand new pieces for us at the time. We hadn't worked

more than a dozen or so poles before we came to a low trestle. Midway across the

span, my father and I both noticed the skunk at the same time. I really wanted

to continue, and tried my best to convince my dad that the skunk was dead, even

to the point of suggesting that we throw stone at it to see if it moved! My

father's wisdom prevailed, however, and I groused all the way home.

As

satisfying as our ground-based efforts were, it wasn't long before our attention

focused skyward at the insulators still on the poles. My father elected not to

climb poles, so we developed a device designed to spin an unwired insulator off

its pin. This simple system was composed of sections of wood handrail, one of

which sported a roughed-up rubber insulator permanently attached to its end. We

fitted the sections together in metal sleeves, assembling a pole appropriate for

the height of the crossarm where the insulator was being removed.

A little

finesse in brushing the rubber tip against the insulator we wanted would slowly

unscrew it, if we were lucky. Then it was popped free, into a baseball glove

wielded by my brother or me. Bottom of the ninth, two outs and bases loaded was

nothing compare to keeping that newest jewel from hitting the ground!

One of my

favorite collecting memories comes from along the Pennsylvania-Reading Seashore

Lines in Pomona, New Jersey. There, the tracks ran parallel to the fence of a

military air base. On the other side of the fence was a frequently patrolled

dirt road, which presented a seemingly insurmountable obstacle to our standard

insulator picking process.

The key to our success at this location was due in

large part to the blackberry bushes growing everywhere along the tracks. We were

also aided by the manner in which the patrol jeep kicked up a highly visible

plume of dust, enabling us to track its location. Whenever the jeep neared, we

stashed our insulator poles in the undergrowth, and made a grand theatrical

production of pretending to pick blackberries. Probably the real clincher to our

orchestrated deception was the fact that we were accompanied by my mother.

It

went down without a hitch, working so well that my brother and I would wave at

the military police as they passed. At days end, the buckets we used for props

were loaded with Gayner 44' s, pointed dome star beehives, and a few Locke 14's.

My father's collecting activities included periodic excursions with two other

collectors in town. They divided up the goodies from their trips on the basis of

a rotating first pick. One of the nicest insulators added to his collection as a

result of these outings was a mint CD 160.7 American in light green.

I recall

the smell of the freshly mown sweet grass greeting me as I stepped out of the

family car to attend my first insulator show, held outdoors on picnic tables in

a Middletown, New York park. My father had attended the Middletown show for a

few years before taking the family along. I had some experience trading by mail

at that point, so it wasn't difficult to jump right into the swing of things at

the show and I added almost two dozen pieces to my collection. One piece that

really thrilled me was an ice aqua Hemingray 50 two piece transposition.

Except from November 1970

Old Bottle Magazine -- Insulator ByLines

I did a

lot of trading in my early collecting years. One of my earliest interests

centered on McLaughlin insulators. By placing and responding to ads in Old

Bottle Magazine and Crown Jewels of the Wire, I managed to assemble a fairly

respectable collection of pieces bearing that embossing. All of my trading correspondence was carried out

through the mail, which I hoped might hide the reality that I was "only a

kid".

My classified ad from Old Bottle Magazine, March 1972

One of the trades I worked hardest at was for a pair of "yellow"

McLaughlins. Unbeknownst to me, my trading partner in this deal readily

recognized that he was dealing with a youngster. In return for a greenish-straw

McLaughlin 19 and a citrine McLaughlin 20, Dee Willitt accepted from me nothing

more than a set of Kerr insulators. At the time, I didn't realize the value of

the citrine pieces, and it was years before I understood the kind gesture Dee

had extended. I know I'm not alone in declaring him among our hobby's finest

personalities. I guess the moral to this story is that you shouldn't let age and

lack of experience stand in the way of your pursuits.

Returning home from school

one day, I was surprised to find John and Carol McDougald visiting with my

parents. They had a Hemingray 19 with a hole clean through it and a machine nut

in the dome. Identified today as CD 186.2, it was without a doubt the neatest

insulator I had ever seen! I'm sure none of us sitting around our dining room

table that day could have envisioned a course of events that would bring us

together again years later, when I periodically, managed to provide research for

this magazine, beginning in 1988.

It turned out that a friend of my father

worked at the Kerr factory in Millville -- a man by the name of Calvin Cobb, Sr.

Although many people claim involvement with the "cobalt splotch" Kerr

DP1, this project would never have happened without Calvin as the driving force

behind it.

Not long after the cobalt splotch insulators were run, my father and

I took them to an insulator show in Bergenfield, New Jersey. Calvin came with

us, and brought along one of the splotches that had broken during annealing. He

used this to demonstrate that the cobalt color ran through the insulator and was

not simply a surface application. We had a five dollar price tag on the

splotches, but no one was interested!

Although we were never successful at

turning Calvin into a true collector, he eventually teamed up with my father to

produce miniature glass insulators. Calvin knew all the appropriate people to make a mold and

get glass into that mold. Thus the Wentzel-Cobb miniature TW was born, followed

soon thereafter by the Holly City miniature DP-1. Only recently has a third

style, the Holly City WC miniature power cable been introduced, but most of that

mold was made during Calvin's lifetime.

Perhaps the greatest contribution Calvin

gave to our hobby took place the day he rescued Kerr's insulator files from the

indignity of the trash can. This material contains documents dating from the

origin of Whitall Tatum insulator production in 1922, and its preservation is

the sole fact that has enabled me to write several articles on Millville-made

insulators.

There was so much information to absorb initially n 18 notebooks

full of data, and thousands of drawings -- that it took me years to recognize

the identity of an insulator which has become one of the centerpieces of my

collection. For many years prior to my acquisition of the "Whitall

Tatum/Armstrong/Kerr Archives", my father carried to every insulator show

he attended, an unembossed clear power insulator which had been cut in half.

This he priced at five dollars. No one ever paid the slightest attention to it,

so he finally gave up and stashed it away in the basement.

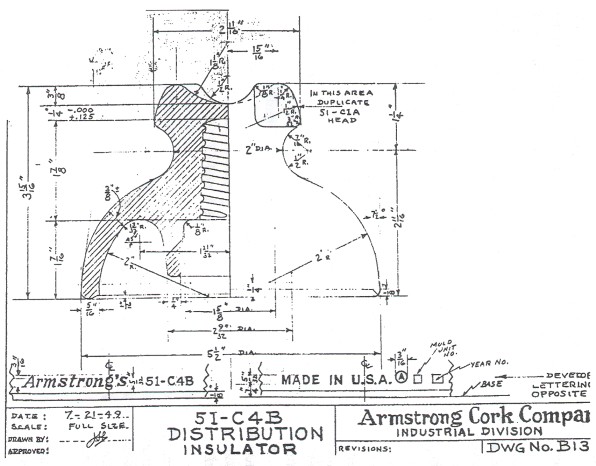

You can only imagine

my excitement when I realized that this outcast matched drawings of a previously

unknown Armstrong insulator, catalogued as number 51C4B. Ultimately, this

insulator appeared in McDougald's Volume II, having been assigned CD 238.2. And,

as if my luck hadn't been good enough, I was even more fortunate later, locating

the other half of this insulator! This side bears the familiar Armstrong circle

A logo embossed on it, in addition to some original factory grease pen markings

identifying it as a "51C4B-Altered"! So there might well be another

version of this insulator to be found. Could I even hope?

In retrospect, this

story has been as much my father's collecting history as it has been mine. It

gave me great joy as a youngster to share this common interest with my dad, as

it still does today.

It's a good thing that he's a patient man, because I'm sure

my exuberance tested him to the limit when I was younger. It was very difficult

for me to pass by any unwired insulator without attempting to retrieve it. On

those occasions when I was denied that opportunity, usually upon spotting an

insulator we already had by the dozens, and, for sake of argument, within sight of a police station, my father's plea of ,

"It's only a beehive, Richard!" was met by this adamant reply:

"Well -- it's probably the RAREST beehive in the world!"

Large Image (152 Kb)

As you look at page 171 of Volume II of McDougald's Insulators book, see if

you can tell that the CD 238.2 is only half an insulator.

|